James K, Eve Essex, Dylan Shir, Leila Bordreuil, and V Manuscript Performing Elektra (Scream Through the Eyes of a Statue) at Issue Project Room, April 2018

Premiering the performance ELEKTRA (Scream Through the Eyes of a Statue) in 2018, the artist James K marked the beginning of her residency at ISSUE, NYC. Deeply rooted in a conscious art practice that has honed her peculiar aesthetic to the fusion of visual and sonic elements, with ELEKTRA, James K explored the female voice considering it as an "X-ray to the bones of sound." Building upon the translation of Sophocles' tragic play Elektra by the renowned poet, essayist, and classical music professor Anne Carson, James K externalizes the inner realm of female vocalization. In collaboration with musicians Eve Essex, Dylan Shir, and Leila Bordreuil, a multifaceted interpretation of the "screams" emerged, expressing the various relations between hysteria and the "gender of sound."

fromheretillnow unveils an exclusive interview conducted by the New York-based poet and artist Eli V Manuscript with James K.

James K by Eli V Manuscript

Statement by Eli

E: To start us off, I’m interested in how you’ve described your work as “conceptualizing the female voice as an X-ray to the bones of sound.”

J: In my recent work, I wanted to have each of the performances reflect personas that I am currently working with. When I say persona, it's not just a character with one backstory. It's more of an emotional, cultural, and historical embodiment -- a fragment made of fragments, taking form through an amalgamation of textures and elements: writing, sonic, visual, movement, performance. Additionally, I’ve been using Anne Carson's “The Gender of Sound” as a departure point. Her text discusses how patriarchy has entrapped female sound, tried to contain it; it’s about female sound in its unbridled form and how and why it's been controlled by patriarchal structures.

E: For your piece Elektra (Scream Through the Eyes of a Statue), you used Carson’s translation of Greek playwright Sophocles’ Electra.

J: Right. I was introduced to her work through her poetry and then got into more of her theoretical writing and then her translations. I approached these pieces as further translations, exploring my current understanding of female sound. I wanted to give complex characterizations to the containers that have been put on female identities, to talk about them and then to also challenge them.

E: In Anne Carson's “The Gender of Sound” -- how do you interpret that gendered sound? Your piece Elektra (Scream Through the Eyes of a Statue) utilizes the scream which Anne Carson separates from traditional uses of language, both in Greek and in her translation into English. In the piece, you focus on those screams which aren't words we are familiar with -- and I’ve heard you mention the scream as being a truly feminine sound.

J: Carson talks about screams in a few ways. I think most importantly, the screams were compared to two other protagonists in Greek mythology. One of them was turned to stone and she used tears to communicate; and the other was transformed into a bird and used birdsong to communicate. Electra’s screams were compared to these, in the sense that they are all modes of female sign language. So, even when any container or walls are put up around vocality, there is still a form to express and electrify through screams. The idea of female sign language is important to me. It is something that I have come to on my own terms and utilized much in my music and art practice, though I had never heard it articulated in this way until I read Carson’s essay on translating Electra. In my Elektra piece there are no lyrics. Even though I'm using Anne Carson's translation of Sophocles’s Electra as the departure point, for the specific work, I wasn't interested in having any of the text be completely legible. This differs from Strauss’ Elektra opera, which sticks to a linear narrative. My intention for this work was in direct opposition to that. I wanted the narrative to exist in a dream logic of layers and layers of materials: sound, visual, written, performative, video, architecture-layers that loop and consume themselves. Layers that have no beginning or end. In every sound, every being, lies a history of everything before them. I wanted the layers to allude to this.

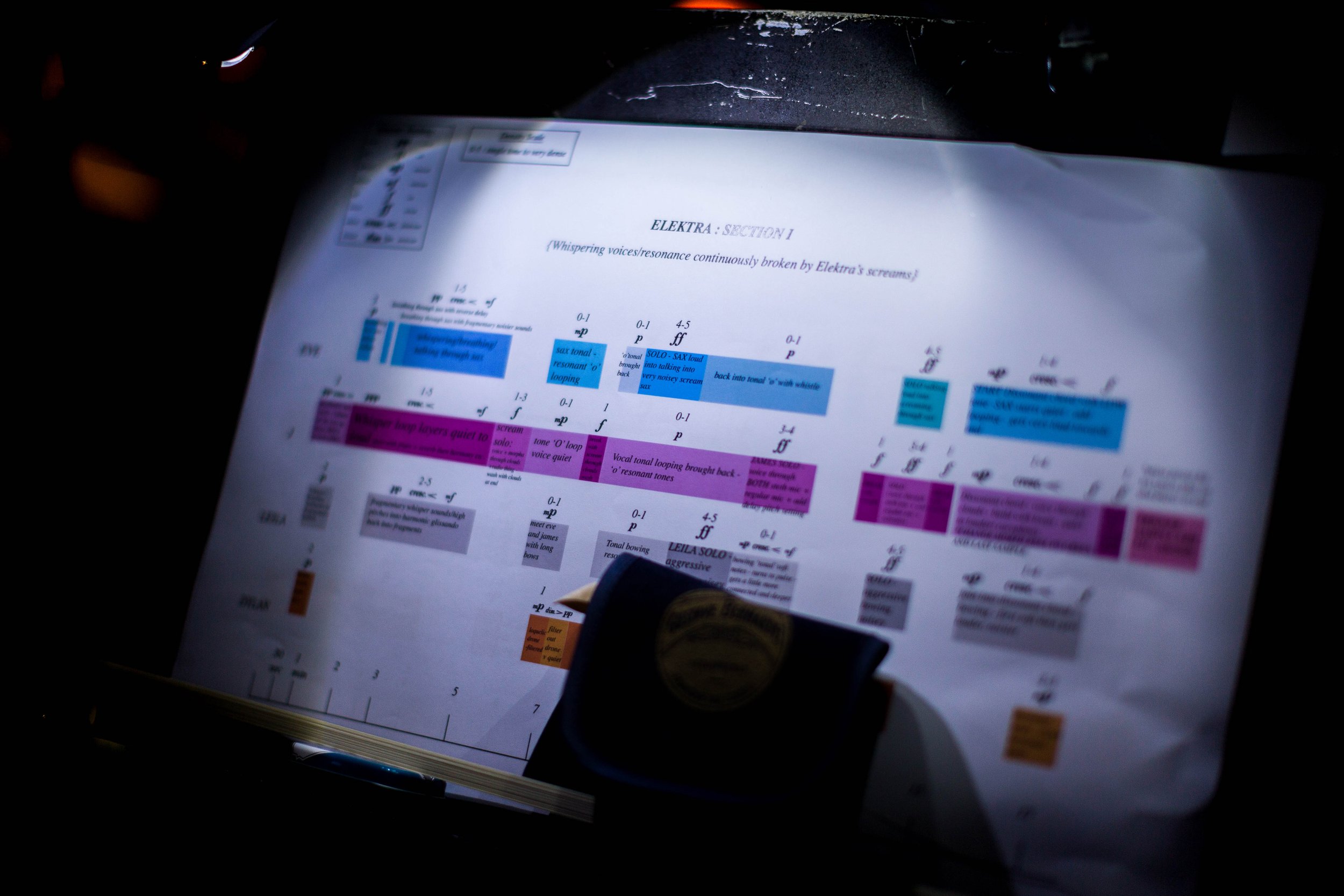

E: How did these layers turn into the score performed?

J: We were collaboratively improvising our translations of Electra’s Screams, and other sections from the text which I translated into improv exercises. From this recorded material, I then constructed a score, to form another, more layered and nonlinear translation of Sophocles. Any language that was in the text was disintegrated. Lyrically, I wanted the vocals in the piece to be other sounds that still communicate feeling or words in some way, without using language.

E: As humans, we've used vocality prior to written language throughout our history through grunts and screams. The slow naming of objects and ideas and actions developed into language amongst different peoples. That eventually formalized into forms of writing. Writing was formed when our oral stories started to become concrete and passed down as these definitive volumes, which eventually transform into law and the many absurd systems we deal with now that use language as an extremely structured and demanding form. In Greece, the era of Elektra, we're talking about a time when language was a little less formalized and we might have been closer to these original forms of vocality. Some people theorize that as writing developed, goddess worship ceased, and that those two paradigms are on a similar arc. It's a spectrum, not a moment, but the spectrum that led away from goddess worship also led to the formalization of language as writing, which became a legal system as opposed to a poetic and expressive system. Do you think that's the core of what you’re doing?

J: Yes, it also becomes a binary when language was solidified in form. Language makes things static, it stabilizes memory and repeats it, and this affects our thinking. Language comes from a reality which is way more fragmented. I'm interested in going back to the fragmentation and the multiplicity instead of the binaries. Elektra is a sensitive being. I feel that these systems are simplifiers, and they promote less sensitivity. The idea of a ‘rational’ mind, is a mind that likes structures instead of feeling. Elektra, and my connection to her, involves my interest in forming language through this hyper-sensitivity. This language, then, is and must be multi-layered, and not having much, if anything to do with what most call ‘reason.’

E: We're talking about the idea of a binary versus a spectrum, and we're using words like woman and feminine. Can you explain a little bit about those ideas being within certain spectrums as opposed to a binary system?

J: I am interested in using those words in reference to language. My idea of what it means to be feminine comes down to a philosophy influenced by a lot of other things. When I was a teenager, I wrote this manifesto called the “Venomist Manifesto.” I was inspired after reading the writings of Donna Haraway and Judith Butler, and to give my own spin on the malleability of identity. In my manifesto, I talk about how many containers for “feminine” exist, and how you can move constantly and demonstrate their multiplicity. It’s about finding truth in layers, in fragmentation, and the amorphous void which both holds and is the venom. For me, this is what is feminine- It is the quality of venom; oozing digestion, the disintegration and movement in the inside that we can't see, but rather feel.

E: One of your personas is a specialist in vomit.

J: Yeah. “Nude Volvo” is a vomit archaeologist and she's discovering fragments of personas in vomit. Another V word.

E: And this is the persona involved in your Elektra piece, or no?

J: Nude Volvo is more of an overarching persona that discovers and translates many of my other personas. She is also a DJ. In ways, she is the one who composes the structure, or scores. She is a mode I use for creating work, though she is not always present in the literal sense. That being said, I have done a few performances where she has been central.

E: Let’s talk more about your approach to the scoring and construction of Elektra.

J: With Elektra, I wanted it to be all women involved in this piece and I wanted it to be conversational in the sense that it is a collaborative framework that I’ve created. I brought each of the players into the space two and a half months before the piece, and we started generating sounds in those first months. Before we met, I gave them Anne Carson’s translation, Sophocles Electra, and some of my notes. I wanted them to have an initial feeling for the content, so they could have some basis for interpretation. In those early generative sessions, we used the screams as a basis: I brought them in individually and gave each of them a scream. There's fourteen screams written with letters: “AIAI” is a scream, “O” is a scream, and then the words get longer: ‘EE AIAI,’ ‘OIMOI TALAINA,’ ‘OTOTOTOTOI TO TOI.’ I had an idea of the sounds that each of the players could be generating, but I wanted them to initiate their decisions. I lifted and created some exercises for improvising. For example, when “Oh” was voiced, I would crescendo, the other person decrescendos, so on and so forth. Another scream, I go from longer and looser notes to more staccato and faster. These exercises were meant to promote conversation sonically. The idea was for each of us to react and translate from our own contained histories, and then through improvising, it becomes a conversation, these histories meld.

J: It was relatively loose. The exercises are simply parameters to start a conversational flow. We interpreted various screams using our instruments. We each had multiple instruments, some overlapping, so the sounds interchanged and moved around quite a bit. For instance, I was using voice, violin and modular synthesizer. There were four of us: myself, Eve Essex, Dylan Shir, and Leila Bordreuil. In terms of the set-up and layout, I positioned us facing each other in a circular form at the center of the space. Our backs were facing the audience, who were seated around, echoing out from our central circle. There were four tvs, staggered between each of us, which were facing out to the audience. They played other video translations, one being a choreography my friend and collaborator, dancer Alex Jacob generated from sounds I gave her. The tvs were the projections facing outwards, while we faced inwards, towards each other. I really wanted it to feel like we were having a conversation, also to visually have it reflect a seance of some kind.

E: On the Seance: Do you see the circle as a feminine form? Can you describe what was in the center of the circle during the piece and describe its purpose?

JK: There's no end point in a circle, it's continuous. A circle could also be a portal or a black hole. It’s also the first scream. In Elektra, related to the loop and to translations, I had my reel-to-reel recorder at the center of the circle. The whole piece started with me pressing play on the reel-to-reel and recording the performance. At the end, I rewound it, amplifying the sound of the reel rewinding. I pressed play, and we exited the stage as the whole recorded piece played back. So, the audience listened to the playback of that experience they just had. The idea is that it’s continuing. It's still moving, still translating.

E: You call that in your notes a collapsing of time.

J: I wanted to avoid an ending because I wanted this piece to exemplify a continuation, an endless infinity of movement.

E: We know that live documents and recorded documents are different. To me, what it symbolizes was that there was the live form and the recorded form, and the looping alludes to the fact that this form will also degenerate. If we go further into time, someone might re-perform your piece and translate it as we know it, and we'll have another version of that form and it's recording, and so on.

J: Yes. This degradation is key to the process of translations. It is what informed my scores.

E: The scores of Elektra are very beautiful. They're very instructive and descriptive, not only in a linear fashion, but also in the poetic description of actions that the musicians and performers will make. The score of Elektra, which I got to experience in real time as a performer, we read instructions which were both written by you and then augmented by the players. There was a lot of performativity and vocality in the way you, Eve, Dylan, and Leila performed.

J: The performativity has to do with us merging with our instruments, translating them into our voices. The idea is that these things are vessels for us to speak, hence “screaming through the eyes of a statue.” The reason why I wanted to work with Eve and Dylan specifically is because we started this band, Hesper, about three years ago. The band is purely improvisational. When we started, I would bring my recording set up and record the jams, so working in this way informed my process and method for composing the final score for Elektra. I wanted to do the piece with them because our conversational relationship sonically had already been established. The other ensemble member was Leila Bordreuil, who has a developed improv practice of her own. She was playing cello. At one point she also played violin through an amplifier. We were all creating many different types of sounds, translations. And the last person performing was you of course, Eli.

E: Yes, you also asked me to interpret the screams. As opposed to a musical or vocal projection of those pieces of language, I represented them through images, the same fourteen screams. When we scream or when we say a word, no matter how loud it is, one visually represents it by putting an exclamation point on it. One can make the text bigger, but it's still the same 26 characters that we've learned to represent language. You had mentioned some of the distortions I’ve done with text and we've worked together on projects before. So, I made the same distortions to amplify those visual characters, as we would amplify a gentle sound into a louder sound.

J: I didn't want the text to be there in blatant form, or too narrative or obvious. I really wanted the text to be another layer or translation. To reflect the sound, I gave you some of the audio that we had been generating and showed you the progression. I also showed you specific sections I had pulled from Carson’s text, my notes, and a book of Sophocles’ Electra in Greek. These were all of the materials I asked you to use to make your visual translations of the audio. I was excited by your work with text, and wanted the text to become more and more disintegrated and layered, as, sonically, the piece progressed and it too became degraded by layers of translations. The text compositions you made, even though I had a clear chronological ordering, I wanted these texts to somehow be performed live. So they were being projected and then you were using prisms to further distort them and perform those distortions live. The performance of these projections, animating them, making them move throughout the space, was all improvised.

E: What do you think gives the screaming of Electra its power?

J: Well, I suppose the scream is a common point of reference for artists working in sound, and people have made scream scores in the past. I was interested in screams primarily because I felt like it was a relatively obvious starting point to translate the gender of sound essay into unbridled sound. For me, it is more about a kind of catharsis. Personally, I use screaming to get rid of any evil, anger or anxiety I feel inside of me. It is the most direct way for me to release. It takes all the trauma, the history of violence we contain in our bodies and materializes it. This materialization is the translation into expression, which in turn communicates. People often get mad at babies’ cries, but that anger is their own fear. As humans we are programed to respond to a baby’s scream, it is an engrained sign of distress. The conditioning which occurs teaches us to hold it in, which causes more suffering. For me, releasing feels like the most honest and primal thing I could possibly do.

E: You have a phrase in some of your unpublished notes that we shared in the early scoring practice, where your cue for yourself was “I will scream again and break this harmony.”

J: Yes, break this harmony. If there's a structure, which is ‘harmony’ in western musical terms, or a container, or door, or the conditioning we all experience, whatever, a scream has the ability to cut through it. That's really why it's powerful. It has the ability to break it down. And it's related to Electra’s entrance. When Electra first appears in the Sophocles version -- and Anne Carson talks about this in her intro about the process of her translating this piece -- Electra enters and she breaks the iambic pentameter. This is really unheard of in Greek mythology. And she continually does that throughout the piece, breaking the iambic pentameter. In the first section of my score, I was really trying to create moments where we all come together in ‘harmony’ and then break that with a scream, or a cut. Just as the breaking can happen with a scream, the scream’s effect can also be translated into the transitions. So in thinking about the transitions, it could be a sharp cut, a car crash collapse, or an intense dissonance. I was using dissonance to establish this communicative collapse.

E: When Electra breaks the pentameter, not only is it a cut in the continuity of pre-existing line, but often it’s cut by a long cluster of vowels, which you can't even figure out how to enunciate properly. In writing, whether it's playwriting or poetry, one has certain access to pre-existing techniques of breaking what would be a normal reading with an elevated or agitated or amplified reading. Some of these techniques exist through other experimenters through time and some of them you invent when you need what doesn't exist.

J: Right.

E: So in regards to Electra talking to herself with these unpronounceable clusters of vowels, we see some of this in the experimental poetry of the last couple centuries. We've developed techniques of learning how to make the page scream when there's not any amplification there. In music, over the past century specifically, we’ve developed a lot of techniques that have allowed us to make what would have been a quieter, more controlled, or more historically harmonious sound become louder, more agitated, or full of rage. We electrified traditionally non-electrical instruments in the mid-20th century, and had electric music. Simultaneously, even before we serialized all twelve notes on the keyboard, we experimented with forms of dissonance. In the 20th century, many composers have taken all of those limits really far -- all the way to full washes of full spectrum sound, the loudest possible sounds all the way to the quietest possible sounds. Can you talk about some of the practices that you utilize to make cacophony? Maybe talk on some of the practices that you use to make those screams scream louder and more dissonant.

J: The cacophony exists in me, in my experience, and all around me. I’ve always wanted to embrace it. There was a brief moment when I was much younger, where I was trained classically in voice. I had a lot of issues with it. Basically, when you're training classically, there's a canon you have to train your voice to. So I used to go to these competitions and they would say okay you got 99.5 or whatever on this, because it was great but it sounded too much like you. I found this very problematic. This is going back to putting containers on the female voice and this idea that this canonized sound has culturally been associated with female beauty and purity. And the notion of purity is a problem as well.

E: Similar to when a translator tries to make a “pure translation”, and how contestable that is.

J: Yes, I was interested in placing a classically-sounding voice right next to another voice, which was not canonized -- the scream. Dissonance can be formed when the classical voice is confronted with something that is unbridled. These contradictions form my truth, and I based the scores around this fragmentation and contradiction. I did a lot of research on experimental scores. Eve Essex gave me folders of many experimental scores dating back one hundred years. I researched them. These scores really demonstrate the flexibility of music notation and point to how it doesn't have to be structured traditionally. A score can be nothing and it can be everything. Overall, I took certain elements from researching these and elements from my own practice, and tried to create a score that would function and be legible for all of us. The score included time cues and explanations for the various improvisations and dynamics, which ultimately provided the structure for the piece. If I was to perform this piece again and make another score, I would like to include the actual screams, or to include sections that are purely visual images that we would have to interpret.

E: Let’s talk for a moment on what's called the Electra chord in your notes.

J: The Electra chord was a chord that Johann Strauss created specifically as a motif when Electra enters the stage in his opera. When it was created it was really controversial because of its dissonance. I wanted to create our own Electra chord. We did it through improvising and feeling/hearing dissonance. Our version of the Electra chord was brought into the composition multiple times, each time varying, of course. I even brought in a recording of Strauss’ chord from the wikipedia page on it, which I then filtered through one of my effects modules, warping it further. The interesting thing, is that when we were generating a dissonant chord, it's really the same concept as creating a harmony with each other. It's interesting because you do feel like there's still a harmony in that dissonance.

E: I'd like to place your performance within a category of having many moments of extreme sound, minimal sound, and experimental sound that certain people trained in music theory and experimental music forms would be able to pick up additional ideas from. But your audience was very mixed. There were people that knew a lot about music and a lot of people that didn't. The age range was like eight to eighty-five and no one walked out of there not absolutely thrilled. So, you somehow found a way to maximize experimentation, yet also not take away from traditionally enjoyable forms of narrative and challenges to those narratives that allowed everyone to follow.

J: There’s a consistent motion towards splintering and layering. Radicality must come from movement. If you can contain it, it isn't radical. Putting things together that wouldn't normally be put together is what I'm trying to do. When you bring together people with different types of histories, narratives, references, and education, whether musical education or not, it's going to create a hybrid where these narratives are seen in fragments within the people and within the piece itself. It’s creating a new narrative and a new translation. In my work if I'm talking about tropes—and not only the obvious tropes, but the unobvious ones, too—as being reflections of greater themes, it’s because these smaller things, the fragmented things, all develop it. I want to continually challenge that history. You can do that by bringing to light the other stories that are underneath the surface that weren’t told or that weren't known.

E: I was unaware originally in the Greek lexicon of heroes and heroines that Electra was a relatively minor, tertiary character. There's no mention of her in Homer’s Epics. Do you have thoughts about her centering as a story?

J: She is minor, but that has nothing to do with her importance. In fact, by the end of Electra she is described as the strongest character, amongst the ‘strongest’ characters, her father being King Agamemnon, a main character from the Iliad.

E: You have these master narratives that are presented in their mythological forms whether poetically or religiously. But, it took Anne Carson translating Electra to re-center the story from how she viewed it through a feminist perspective. We're taking minor characters from master narratives and re-centering those narratives to understand a greater scope of their feelings, and realizing that every minor and even absent characters hold their own master narrative with as full range of life and story and emotions as the characters that were presented as major originally.

J: Exactly. Histories aren't fixed. You can illuminate that by bringing to light the other stories that are underneath the surface that weren’t told or that weren't known.

E: We know that entire histories are told by the winners of wars and how they committed that story to print. We have the same issue in poetic narratives, whether through religious mythos or poetic verse. So to find the stories of those whom weren't committed to print, we become more reliant on oral histories as opposed to written histories that are presented as some truth or legal document, when of course they were once an oral history as well.

J: When Anne Carson translates, it sounds like Anne Carson, it's her voice and it's beautiful. She updates it into something that resonates for now. She talks about her process of translation-she has this recurring dream while translating Electra, where she's in a glass house trying to find the word for this Greek word, and she’s hovering over the word, but then it shatters and falls before she can see. That feeling is the feeling that I want to lean into. I don't think there is one word for this. And that's what's cool about her talking about translating something so ancient --these words don't exist anymore. There is no one word for that Greek word. That Greek word meant something in that society that is now lost to our minds.

E: A translator who imagines they're doing some pure translation, finding the correct word for every word, finding the correct passage for every passage - is obviously setting themselves up for failure. Poetic sensibilities and political ideologies, everything about you is part of that translation. Anne Carson allows the veil to be lifted. We know we are reading both her poetry and a specific interpretation of a classic text through reading her translation.

J: Exactly. And with my translation, the idea is that there isn't one scream for “O,” that first scream. There are multiple screams. That's why there are multiple people creating these screams. For every word, there could be, and are an infinite amount of layers to that word. And that's what I wanted to show.

E: You have! simultaneously through voice, through instrument, through pre-recorded passages, and through visuals. For Elektra, these tools represent the victory of female sign language. These are women who have left behind human form and rational speech and yet have not let go of the making of meaning.

ISSUE Project Room's annual Artist-in-Residence program provides New York-based emerging artists with a year of support, offering artists access to facilities, equipment, documentation, pr/marketing, curatorial and technical expertise to develop and present significant new works, reach the next stage in their artistic development, and gain exposure to a broad public audience.

![[1] Jorge Luis Borges, El Aleph , trans. Normam Thomas Di Giovani in collaboration with the author. First published in Sur (1945). [2] Ibid [3] OOO stands for Objects Oriented Ontology, a Heideggerian school of thought that rejects the privileging…](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5433ef4de4b0802bfd48201b/1611164424990-KJQ2EZDZBNCI8RLXBCX6/spacer.jpg)